|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Talks & Events

|

Colloquia: 2019

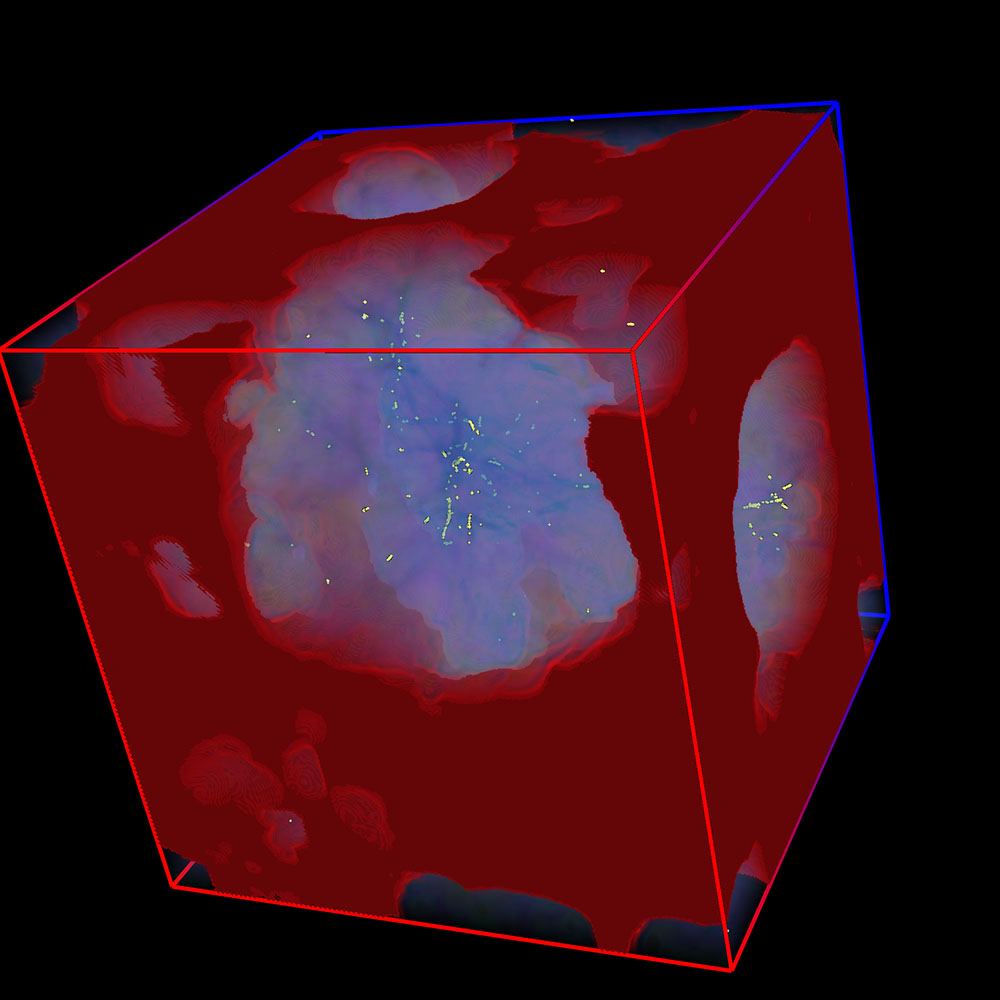

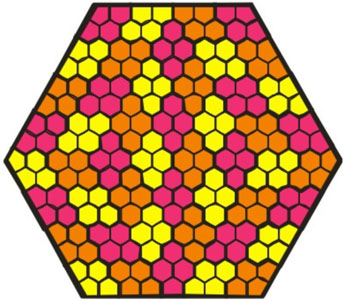

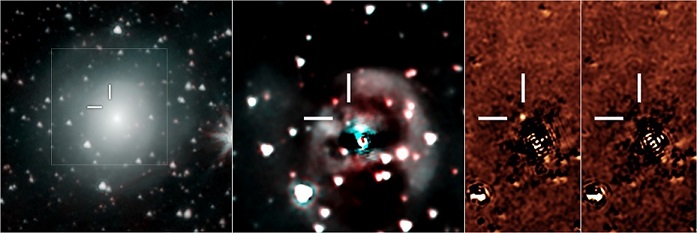

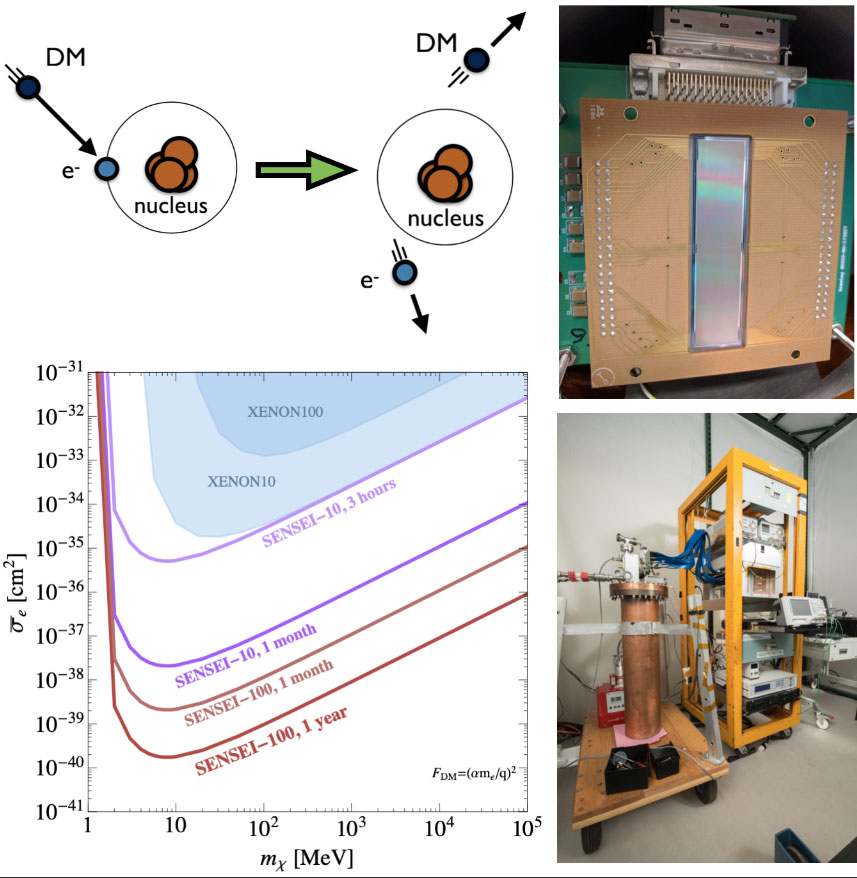

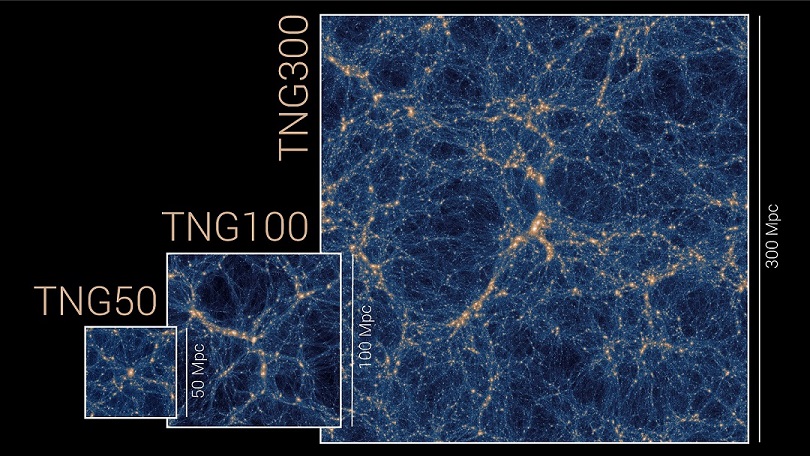

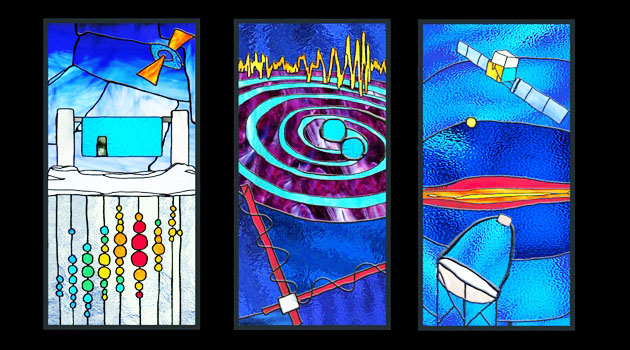

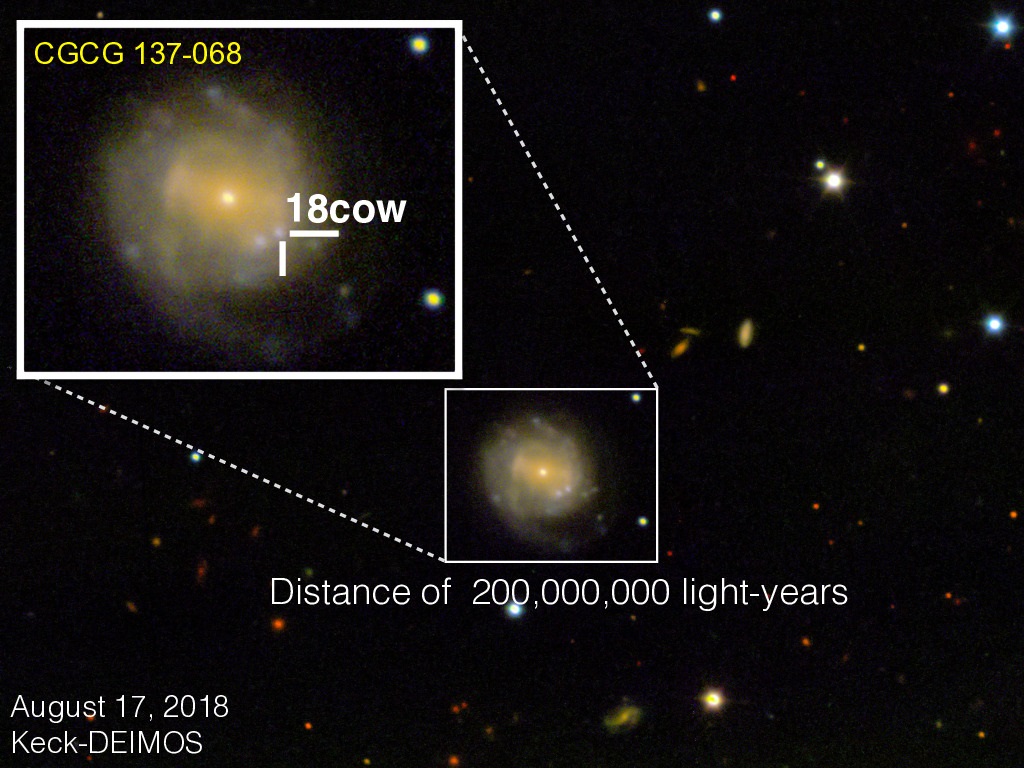

How many numbers does it take to determine our Universe? Video Since 2013, the Planck Surveyor team has made a good case that it takes six numbers to describe the whole Universe (fewer than the ten digits in a phone number), based upon their all-sky map of the CMB. Others have different opinions: zero, one, two, six (a different), and nine to describe our Universe. As I will discuss, the choice of numbers reveals much about what we know and our aspirations, as well as how we think about the Universe. After exploring the landscape, I will advocate for zero numbers and discuss the path and strategy to get there. Cosmic Reionization Cosmic reionization - ionization of the bulk of cosmic gas by ultraviolet radiation from first galaxies and quasars - is the least explored epoch in cosmic history. While significant progress has been made recently with the HST Frontier Fields program, the major breakthrough is still in the future, but not a distant one. The launch of JWST will start a revolution in studies of cosmic reionization, and other advanced observational probes will follow soon. As observers are preparing for the flood of new data, theorists are currently busy revamping their tools to stay on par with future observations. This fortunate match between theory and observations will lead to a major breakthrough in this last cosmic frontier. A New Frontier in the Search for Dark Matter Video The gravitational evidence for the existence of dark matter is overwhelming; observations of galactic rotation curves, the CMB power spectrum, and light element abundances independently suggest that over 80% of all matter is "dark" and beyond the scope of the Standard Model. However, its particle nature is currently unknown, so discovering its potential non-gravitational interactions is a major priority in fundamental physics. In this talk, I will survey the landscape of light dark matter theories and and introduce an emerging field of fixed-target experiments that are poised to cover hitherto unexplored dark matter candidates with MeV-GeV masses. These new techniques involve direct dark matter production with proton, electron, and *muon* beams at various facilities including Fermilab, CERN, SLAC, and JLab. Exploring this mass range is essential for fully testing a broad, predictive class of theories in which dark matter abundance arises from dark-visible interactions in thermal equilibrium in the early universe. The Planck last release Video The Planck High frequency maps improvements will be described together with some of their associated cosmology results. Implications for future experiments will also be discussed. Extreme Astrophysics The electromagnetic spectrum has been opened up from meter radio waves to 100 TeV photons and augmented with 10 - 300 Hz gravitational wave, MeV - PeV neutrinos and MeV - ZeV (160 Joule) cosmic ray messages. Consequently, there is a high rate of discovery and understanding of phenomena whose explanation invokes accepted physics - classical (including general relativity), atomic, nuclear and particle (including QED) processes - in extreme environments. The richness of the discovery space can be epitomized by describing some new observations and ideas pertaining to relativistic jets formed by massive spinning black holes, Ultra High Energy Cosmic Rays accelerated by strong shock waves surrounding rich clusters of galaxies and Fast Radio Bursts, generated by neutron stars with 100 GT magnetic fields. Constraints on Quantum Gravity Video Superstring theory is our best candidate for the ultimate unification of general relativity and quantum mechanics. Although predictions of the theory are typically at extremely high energy and out of reach of current experiments and observations, several non-trivial constraints on its low energy effective theory have been found. Because of the unusual ultraviolet behavior of gravitational theory, the standard argument for separation of scales may not work for gravity, leading to robust low energy predictions of consistency requirements at high energy. In this colloquium talk, I will start by explaining why the unification of general relativity and quantum mechanics has been difficult. After introducing the holographic principle as our guide to the unification, I will discuss its use in finding constraints on symmetry in quantum gravity. I will also discuss other conjectures on low energy effective theories, collectively called swampland conditions, with various levels of rigors. They include the weak gravity conjecture, which gives a lower bound on Coulomb-type forces relative to the gravitational force, and the distance conjecture, which is about structure of the space of scalar fields. I will discuss consequences of the conjectures. The Dynamic Infrared Sky The dynamic infrared sky is hitherto largely unexplored. The infrared is key to understand elusive stellar fates that are opaque, cold or dusty. The infrared unveiled the otherwise opaque heavy element nucleosynthesis in neutron star mergers. I will describe multiple projects to chart the time-domain in the infrared. I will begin with the SPitzer InfraRed Intensive Transients Survey (SPIRITS) −−− a systematic search of 194 nearby galaxies within 30 Mpc, on timescales ranging between a week to a year, to a depth of 20 mag with Spitzer's IRAC camera. SPIRITS has already uncovered over 131 explosive transients and over 2536 strong variables. Of these, 64 infrared transients are especially interesting as they have no optical counterparts whatsoever even with deep limits from Keck and HST. Interpretation of these new discoveries may include (i) deeply enshrouded supernovae, (ii) stellar mergers with dusty winds, (iii) 8--10 solar mass stars experiencing e-capture induced collapse in their cores, (iv) the birth of massive binaries that drive shocks in their molecular cloud, or (v) formation of stellar mass black holes. Motivated by the treasure trove of SPIRITS discoveries, we just commissioned Palomar Gattini-IR - a new 25 sq deg J-band camera to robotically chart the dynamic infrared sky. We have also begun building WINTER - a new 1 sq deg yJH-band camera on a new 1m telescope at Palomar Observatory. Direct Detection of sub-GeV Dark Matter: A New Frontier Video Dark matter makes up 85% of the matter in our Universe, but we have yet to learn its identity. While most experimental searches focus on Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs) with masses above the proton (about 1 GeV/c^2), the theoretical landscape of possible dark-matter candidates has expanded significantly over the last decade, to consider masses from 10^-22 eV/c^2 up to the Planck mass, and even higher in the case of composite dark matter. A broad search program is therefore needed to maximize our chances of identifying dark matter. In this talk, I will discuss the search for dark matter with masses between about 500 keV/c^2 to 1 GeV/c^2, which has seen tremendous progress in the last few years. I will describe several direct-detection strategies that can probe this under-explored mass range, including searching for dark matter interactions with electrons in noble liquids, semiconductors, and scintillators, as well as searching for interactions with molecules to excite vibrational states. I will in particular highlight SENSEI, a funded experiment that will use new ultra-low-threshold silicon CCD detectors ("Skipper CCDs"). I will describe the first results from SENSEI and show how SENSEI, and the upcoming DAMIC-M, will probe vast new regions of parameter space in the next few years. I will also mention how placing a Skipper CCD on a satellite could probe strongly interacting sub-GeV dark matter. Simulating Galaxy Formation: Illustris, IllustrisTNG and Beyond Cosmological simulations of galaxy formation have evolved significantly over the last years. In my talk, I will describe recent efforts to model the large-scale distribution of galaxies with cosmological hydrodynamics simulations. I will focus on the Illustris simulation, and our new simulation campaign, the IllustrisTNG project. After demonstrating the success of these simulations in terms of reproducing an enormous amount of observational data, I will also talk about their limitations and directions for further improvements over the next couple of years. Why doesn't the Solar System have close-in super-Earths? Jupiter is the only planet in our system that would be detectable if the Sun were observed from afar with current instruments. Its wide, near-circular orbit makes it a ~10% rarity among known giant exoplanets and the Solar System a ~1% rarity among Sun-like stars. Another oddity of the Solar System is the absence of close-in super-Earths, which are found around a significant fraction (~50%) of main sequence stars. Models for the origin of close-in super-Earths can match the distributions of observed systems, although the compositions of super-Earths (icy vs rocky) are a key constraint. However, models are generally too efficient, and cannot explain systems like ours without super-Earths. Jupiter's growth may provide an answer. If Jupiter's core formed quickly, it would have blocked the flux of small `pebbles' drifting inward through the disk and starved the terrestrial planets' building blocks. Once Jupiter was fully-grown it opened a gap in the Sun's protoplanetary disk and may have blocked the inward migration of larger cores, protecting the inner Solar System from icy invaders than instead formed the ice giants and Saturn's core. These ideas remain incomplete but have the promise to explain how the Solar System fits in the larger context. The Search for Biosignature Gases on Exoplanets Thousands of exoplanets are known to orbit nearby stars and small rocky planets are established to be common. The ambitious goal of identifying a habitable or inhabited world is within reach. But how likely are we to succeed? We need to first discover a pool of planets in their host star's "extended" habitable zone and second observe their atmospheres in detail to identify the presence of water vapor, a requirement for all life as we know it. Life must not only exist on one of those planets, but the life must produce "biosignature gases" that are spectroscopically active, and we need to be able to sort through a growing list of false-positive scenarios with what is likely to be limited data. The race to find habitable exoplanets has accelerated with the realization that "big Earths" transiting small stars can be both discovered and characterized with current technology, such that the James Webb Space Telescope has a chance to be the first to provide evidence of biosignature gases. Transiting exoplanets require a fortuitous alignment and the fast-track approach is therefore only the first step in a long journey. The next step is sophisticated starlight suppression techniques for large ground-and space-based based telescopes to observe small exoplanets directly. These ideas will lead us down a path to where future generations will implement very large space-based telescopes to search thousands of all types of stars for hundreds of Earths to find signs of life amidst a yet unknown range of planetary environments. What will it take to identify such habitable worlds with the observations and theoretical tools available to us? WIMP Dark Matter - dead or alive? Video The hunt for the identity of dark matter continues with undiminished strength, even though the most popular candidate during recent decades, the Weakly Interacting Massive Particle (WIMP), is facing pressure from non-observation in present-day experiments. In this talk, a review of the situation, discussing some of the WIMP and non-WIMP possibilities, will be given and of some intriguing indications of signals be discussed that may in fact point to the survival of WIMP dark matter. Upcoming experiments may clarify in the next few years whether the dark matter problem thus has been solved, or if a change of paradigm is needed. Advancing CMB Cosmology: ACTPol and onward to CMB-S4 Video Measurements of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) are a powerful probe of the origin, contents, and evolution of our Universe. CMB measurements continue to improve according to a Moore's law under which the mapping speed of experiments improves by an order of magnitude roughly every five years. This rapid progression in our ability to measure the CMB has translated into a series of scientific advances including showing our universe to be spatially flat, constraining inflationary and alternative theories of the primordial universe, and providing a cornerstone for our precision knowledge of the Lambda-CDM model. Observations with the current generation of experiments, including Advanced ACTPol, will soon produce improved cosmological constraints. Building on this work, in the coming decade CMB-S4 will: pass critical thresholds in constraints on inflation and light relativistic species; provide improved measurements of dark energy, dark matter, neutrino masses, and a variety of astrophysical phenomena; and enable searches for new surprises. In this talk I present the design and status of measurements with Advanced ACTPol and how we are building on this work to realize the next generations of experiments including Simons Observatory and ultimately CMB-S4. I will highlight the technological advances that underlie the rapid progress in measurements including: polarization sensitive detectors which simultaneously observe in multiple colors; metamaterial antireflection coated lenses and polarization modulators; and overall advances in experimental design. I will present preliminary new results from ACTPol and conclude with science forecasts for CMB-S4. Can Big Data Lead an Inclusion Revolution? Ground-based astronomy research is evolving into an era of large surveys and big datasets. With the help of federal funding, many of these datasets are already accessible through public archives and databases. The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, expected to begin Science Verification in 2021, will be the flagship ground-based facility into the next decade, surveying the accessible sky and delivering 200 petabytes of data over ten years. The survey is an opportunity for a research 'inclusion revolution' by providing data and data products for use by all members of the community. However, this revolution can only be realized if 1) data products are not just accessible, but discoverable and easily useable, and 2) if the broad community of astronomers is prepared to use tools and services to take advantage of these datasets for achieving science goals. At NOAO we are actively engaged in several programs to support broad community use of current data holdings and near-term public surveys as we prepare for the big data sets that will flow once the LSST survey begins. In this talk, I will describe these efforts and the challenges of leading an inclusion revolution. Progress with the Giant Magellan Telescope Video The Giant Magellan Telescope is in the construction phase in north-central Chile. I will provide an update on the status of the project and its potential in fields from exoplanets to first-light in the universe. I will also discuss community wide efforts to develop a case for federal participation in the project. The Schmidt Law at Sixty Sixty years have passed since Maarten Schmidt's conjecture that star formation in galaxies was closely coupled to gas density, and since that time the Schmidt law has become an indispensable tool for interpreting, modeling, and simulating large-scale star formation in galaxies. Despite its success as a sub-grid "recipe" for the star formation rate, however, we remain far away from an ab initio theory of star formation, or even a clear understanding of the observed scaling laws themselves. This talk will review the current state of our observational understanding of star formation in galaxies, and the complexity which lies beneath the surface of the observed SFR scaling relations. We are witnessing an observational and theoretical renaissance in the subject, as multi-wavelength observations reveal the multi-scale nature of the star formation process and the complex interactions which are taking place between cosmological, gravitational, interstellar, and stellar feedback processes on these different scales. The picture which emerges is one in which the superficially simple star formation scaling laws are manifestations of a highly dynamic, complex, and self-regulating ecosystem in galactic disks. The multi-messenger astrophysics revolution enabled by neutrinos, gravitational waves, and gamma rays In the past few years, the idea of studying high-energy astrophysics with cosmic messengers beyond those of the electromagnetic spectrum has become a reality. The IceCube Neutrino Observatory has discovered and characterized a flux of high-energy astrophysical neutrinos, and LIGO/Virgo have directly detected gravitational waves. Multiple messengers have been used to study individual astrophysical sources including a binary neutron star merger and an energetic blazar. Within the electromagnetic spectrum, high-energy and very-high-energy gamma rays provide an essential link to the newer messengers. I will give my personal view of this quickly developing field, focusing on time domain astronomy with IceCube and the recently inaugurated prototype Schwarzschild Couder Telescope, a TeV gamma-ray instrument demonstrating innovative technology as a pathfinder for the Cherenkov Telescope Array. Infrared Spectroscopy of Stars and Planets Extrasolar planets and cool stars emit most of their light beyond the range of standard optical observations. These objects are often best studied using infrared spectroscopy. I will present recent results from my group on two topics: space-based IR spectroscopy of exoplanet atmospheres, and ground-based, high-resolution spectroscopy of both planets and stars. I will also conclude with a brief discussing of how future IR-optimized observatories will also enable exciting new science in these areas. Doping - not just for cyclists After a series of null results from the LHC and large direct detection experiments, dark matter remains frustratingly mysterious, and much of the canonical heavy WIMP parameter space is now ruled out. In this talk, I will give an update on the status of the LZ experiment, and discuss an idea to expand the parameter space that can be probed by large liquid xenon TPCs like LZ by adding hydrogen to the target, opening up sensitivity to WIMP masses well below 1 GeV. Galaxies in the Reionization Era Over the past decade, deep infrared images have pushed the cosmic frontier back to just 500 million years after the Big Bang, delivering the first large sample of galaxies at redshifts 7 AI In the Sky: Implications and Challenges for the use of Artificial Intelligence in Astrophysics and in Society Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers to a set of techniques --- like machine learning, deep learning, and data science --- that rely on the data itself to develop models of observed phenomena. AI algorithms have a long history of development, and there has been a recent resurgence in their research and deployment, marked by extraordinary results in many contexts, including scientific ones. However, these algorithms are far from a panacea for our challenging data-modeling tasks. Three major changes have revolutionized the role of data in our lives: 1) the increased availability of large data sets; 2) advancements in computing hardware; and 3) insights for new mathematical and algorithmic techniques. Because of these elements, AI now permeates society --- from the promise of self-driving vehicles to entertainment choices to cancer-detection and criminal justice. Moreover, in the last few years, it has had substantial impacts on molecular chemistry, particle physics, and more recently astronomy. AI is more than likely here to stay, as well as grow as an important technique in our science toolboxes. Nevertheless, AI has significant challenges for reaching its full potential for scientific impact --- namely, uncertainty quantification, interpretability, bias, and hybridization with physical models. These challenges also plague implementations in other contexts throughout society. Given these challenges, how do we implement these algorithms in a responsible, careful, and systematic way? We'll discuss these topics in the context of deep learning and its application to modern astronomical surveys. Finally, we'll discuss the implications for the widespread use of AI in society. Hubble, Chicago, and the Search for Life in the Universe The Hubble Space Telescope story has been a fascinating study in public policy, engineering, ethics, and science. The Hubble is perhaps the most productive scientific instrument ever created by humans. In May 2009, a team of astronauts flew to the Hubble Space Telescope on space shuttle Atlantis. On their 13-day mission and over the course of 5 spacewalks they completed an extreme makeover of the orbiting observatory. They installed the Wide Field Camera-3, the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph, repaired the Advanced Camera for Surveys and the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph, as well as a number of maintenance activities. These Hubble spacewalks are considered the most challenging and daring efforts ever of people working in space. This mission also carried a bit of the University of Chicago with it on board. Now, still going strong on orbit, the Hubble has a full complement of instruments capable of performing state-of-the-art observations from the near infra-red to the ultraviolet end of the spectrum. In this talk we will present a narrative of the adventure, and a look at what some of the scientific results may offer in the search for life beyond Earth in our Solar System. Axions from the Lab to the Cosmos As the gravitational evidence for the existence of dark matter accumulates inexorably, the particle identity of dark matter remains mysterious. One of the best theoretically-motivated dark matter candidates, with some of the most interesting experimental signals, is the axion. Axions are expected to interact very weakly with electromagnetism, which leads to the possibility of detecting axions through conversion to photons in strong magnetic fields. I will review the status of several new experiments and searches aiming to detect axion dark matter on Earth, in astrophysical systems, and produced in the laboratory. Galactic Archaeology: Galaxy Formation and Nucleosynthesis Galactic archaeology is the use of the velocities and abundances of stars to learn about the history of galaxy formation and nucleosynthesis. I will tell three stories of galactic archaeology with three different groups of elements: alpha elements, the iron peak, and the r-process. First, I will present detailed abundances of individual stars in the dwarf satellites, stellar streams, and smooth halo of M31. The evolution of [alpha/Fe] in these stars supports the hierarchical assembly paradigm of galaxy formation. Second, I will present abundances of manganese and nickel in dwarf satellite galaxies of the Milky Way. These abundances are best explained by a strong contribution of sub-Chandrasekhar-mass Type Ia supernovae. Third, I will present measurements of barium abundances in the globular cluster M15. The constancy of barium from the main sequence to the red giant branch indicates that the stars in M15 were born with their unusually large dispersion of r-process elements rather than acquiring it from an external source. Tension in the Hubble Constant Discovery frontiers in the new era of Time Domain Multi-Messenger Astrophysics New and improved observational facilities are sampling the night sky with unprecedented temporal cadence and sensitivity across the electromagnetic spectrum. This exercise led to the discovery of new types of astronomical transients and revolutionized our understanding of phenomena that we thought we already knew. In this talk I will review some very recent developments in the field that resulted from the capability to acquire a true panchromatic view of the most extreme stellar deaths in nature, including the new class of fast and blue optical transients and extreme episodes of mass-loss in the years leading up to stellar death New Probes of Old Structure: Cosmology with 21cm Intensity Mapping and the Cosmic Microwave Background Current cosmological measurements have left us with deep questions about our Universe: What caused the expansion of the Universe at the earliest times? How did structure form? What is Dark Energy and does it evolve with time? New experiments like CHIME, HIRAX, and ACTPol are poised to address these questions through 3-dimensional maps of structure and measurements of the polarized Cosmic Microwave Background. In this talk, I will describe how we will use 21cm intensity measurements from CHIME and HIRAX to place sensitive constraints on Dark Energy between redshifts 0.8 -- 2.5, a poorly probed era corresponding to when Dark Energy began to impact the expansion history of the Universe. I will also discuss how we will use data from new CMB instruments to constrain cosmological parameters like the total neutrino mass and probe structure at late times. |